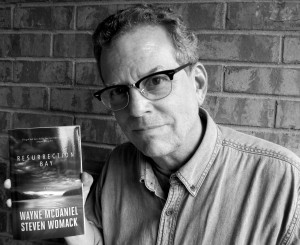

I recently finished a wonderfully successful collaboration on a novel with Wayne McDaniel, a very gifted screenwriter who lives in New York City. At some point, I want to write about how our project—a novelization of his screenplay Resurrection Bay—came about, but for now I want to give some thought to a writing issue that came up when we were in the very last part of the rewriting process.

There’s a character in Resurrection Bay who’s in the military and holds the rank of Captain. In a conversation with another character, our Captain mentions that she graduated from Officer Candidate School three years earlier…

Wait, I thought. Three years? That seems awfully quick to make Captain. Better check that out. So I jumped on a search engine and typed: How long does it take to make Captain in the Army?

Half a second later, I escaped the embarrassment of another story screw-up. Generally, it takes at least four years to make Captain once you’re out of O.C.S. And, one website noted, promotion to Captain at the end of four years is often used as an enticement to reenlist.

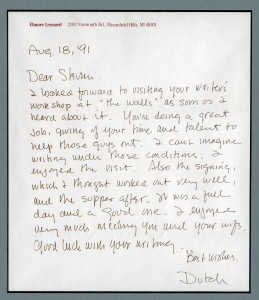

So I went back to the manuscript, made a minor copyedit, and dodged a bullet. It’s always embarrassing to make those kinds of mistakes in fiction. It reminded me of the time when I taught a writing workshop at the Tennessee State Prison here in Nashville. As part of the group, I read from my own work. Since I write crime fiction, I brought a few pages from my latest work-in-progress. I read a scene where a character pulls out a revolver, flicks off the safety, and fires.

Seconds later, a literal wave of laughter ran through the room. These guys were howling. Red-faced, I looked up: “What?” Finally, one of the guys regained enough control of himself to explain to me that revolvers don’t have safeties.

Embarrassing, yes, but in the great scheme of things, a relatively minor and easily fixable screw-up. But what about major screw-ups: plot holes big enough to drive a tank through, historical mistakes that are so massive they ought to sink the whole story, even complete b.s./nonsense?

Well, one might offer, this is fiction. By definition, it’s made up. Someone once asked me what I do for a living and I answered that I’m a professional liar. I make stuff up that doesn’t exist and isn’t true, and I try to do it well enough that for a brief period of time, you as the reader or viewer will buy into it.

It’s why the great Larry Block entitled one of the best books I’ve ever read about writing Telling Lies For Fun And Profit.

That’s really the secret, isn’t it? Doing it so well that you don’t get caught and make a buck in the process…

As proof, let me offer up three stories—all told in the format of the motion picture—that demonstrate beautifully how one can lie one’s arse off and get away with it. Each of these three movies was very successful; even to some extent, classics. And yet each one of them is founded on a plot hole that is so glaring, so egregious, that you wonder how the writers managed to get away with it.

And yet they did…

First off, let’s look at Casablanca. Released in 1942, this film is clearly a classic, so much so that on the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 greatest films ever made, Casablanca is number two, just behind Citizen Kane. Written by the Epstein Brothers—Julius and Phillip—and Howard Koch, Casablanca is a love story set in World War II and centers around the romance of Rick Blaine and Ilsa Lund, two tragic lovers who lose each other and then find each other once again in the chaos and terror of dodging the evil Nazis.

The central story device in this movie is what Alfred Hitchcock called a McGuffin. A McGuffin is something in the story that everyone seems to be after, that all the action revolves around, and yet in the end turns out to be not so important after all.

In Casablanca, the McGuffin is the Letters of Transit. Everyone’s after the Letters of Transit because they guarantee you, as a war refugee, free and safe passage to America. As Rick says, “As long as I’ve got these letters, I’ll never be lonely.”

And, as the Peter Lorre character, Ugarte—who stole the Letters of Transit in the first place—explains, the Letters of Transit are signed by General de Gaulle. They cannot be rescinded, cannot even be questioned. If you’ve got those letters, then it’s a universal Get-Out-Of-Jail-Free card. They guarantee you passage through the German lines, and in the end, Victor and Ilsa get away because they have those letters. As Rick says, at last the Germans are only a minor annoyance.

Great, fine, a wonderful movie, but wait!

Huh? Run that by me again… How does the premise of Casablanca stack up against historical reality?

In the Spring of 1940, the war had been going on for about six months. The winter of 1939-1940 was a time of relative inactivity, a time that came to be known as the Sitzkreig. Then the Germans attacked all across a broad western front and by June, the French folded. They surrendered, the war came to a brief halt, and the Nazis occupied much of the north of France, while in the south, the puppet Vichy government took over.

At the time of surrender, all French soldiers were ordered to lay down their weapons and capitulate. Virtually all of them did, with one notable exception: General de Gaulle. Charles de Gaulle defied orders, rejected the armistice, and escaped to Britain, where he spent the rest of the war making anti-Nazi propaganda broadcasts and leading the Free French resistance.

So in the eyes of the French government and the German Reich, what was General Charles de Gaulle?

The answer is simple: General de Gaulle was a traitor. He was a wanted man, a criminal with a very large price on his head.

So, in the end, the entire premise of Casablanca is nonsense. Not only would Letters of Transit signed by General de Gaulle not get you through a Nazi checkpoint, they would be a virtual death sentence. If Casablanca adhered to historical reality, the best thing Victor and Ilsa could have done with the Letters of Transit was pull out their cigarette lighters and set fire to them. Quickly…

And yet, the movie works. We’re sucked in, completely. Why? Because the guys that wrote the script were the best.

Let’s look at another great film, Thelma and Louise. The script, written by Callie Khouri, won her an Oscar for Best Screenplay in 1992. I love this film and I teach it regularly here at The Watkins Film School. But there’s something about the film that’s never made sense to me.

Thelma and Louise are both women who are shackled by life, and especially by the men around them. The younger Thelma’s husband, Darryl, is an abusive, sexist, mean-spirited regional manager for a car dealer. He’s also a polyester-wearing womanizer. Louise, who is in a tortured relationship with her boyfriend, struggles to make ends meet slinging hash in a cheap diner.

They decide they need a weekend away from it all and take off. On their journey, the playful, frisky Thelma begs Louise to stop at a roadside honky-tonk for a drink. Louise is reluctant, but finally accepts Thelma’s Call To Adventure (to get all Joseph Campbelly on you). In the dingy redneck saloon, they meet Harlan, a seemingly cheerful redneck barfly who’s a classic Shapeshifter (again with the Joseph Campbell). Thelma gets drunk and dances with Harlan, who spins her around until she gets dizzy.

He offers to take her out to the parking lot for a breath of fresh air. Once outside, he starts putting the moves on Thelma, and when she resists, the scene gets ugly. He slaps Thelma around, brutalizes her, and is just about to rape her when Louise appears behind them, pistol in hand.

She rescues Thelma and it looks like Harlan’s going to back down. But then Harlan cops an attitude with her, spouts out a few vulgar lines of dialogue, and Louise blows him away. Thelma and Louise jump in the car and take off, beginning their road trip/journey to escape that leads ultimately to an event that’s either their destruction or their ultimate liberation, depending on your interpretation (Callie Khouri has always insisted that it was the latter).

Great! Wonderful movie! Stack up those awards.

But wait… Something’s bugging me here. Let’s step back and look at this.

When Louise walks outside looking for Thelma, what does she see? She sees her best friend bent over the back of a car with this redneck jerk beating the crap out of her. She’s beaten, bruised, sobbing hysterically, her clothes ripped and torn. Doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure this one out.

So Louise pulls a pistol and breaks up the assault. She delivers to Harlan what can only be described as a stern lecture on how to treat women, and then she backs off, ready to get in the car and go.

But Harlan (who is the living embodiment of the old Southern saying he needed killing) can’t let it go. He starts verbally abusing Louise and Thelma again, in a vulgar fashion that doesn’t bear repeating here. He even makes what could easily be seen as a threatening gesture toward them. So Louise shoots him.

If Thelma and Louise had run back into the bar, screamed for help, called 911, and then explained to the police what had actually happened (with all the other witnesses who would have testified to Harlan’s reputation as a complete asshole), the shooting would almost certainly be dismissed as self-defense. All the police had to do was take one look at Thelma and the two would be merrily on their way, with Louise branded a hero.

Okay, this would have made for one short movie, and Callie could have forgotten that whole Oscar thing. So it turned out for the best. That doesn’t excuse the fact, though, that the premise of Thelma and Louise has a pretty basic flaw.

Guess what? It doesn’t matter. Superb writing and incredible filmmaking gets us past that. Almost everyone I’ve ever talked to about this movie didn’t even notice.

Finally, here’s a movie that by almost anyone’s standards is not a classic: Con Air. Written by Scott Rosenberg (check out his www.IMDB.com entry), Con Air is a commercially successful but incredibly awful guilty pleasure. It’s big-budget, big-star, cast-of-thousands Hollywood filmmaking at its silliest, with Nicholas Cage delivering the single worst Southern accent ever put on screen in the entire history of cinema (On any othah day, that mite seem stray-ange…).

Con Air is the story of Cameron Poe, a decorated war hero who returns to rural Alabama with a chest full of medals. His pregnant wife, Tricia (Poe’s Hummin’bird), waits tables in a grungy redneck bar. Poe surprises her and they have a wonderful Kodak moment, which is interrupted by a table of obnoxious, drunk rednecks. Tricia begs Poe not to mop the floor with them, and he stands down.

Later, in a dark parking lot on a rainy night, the three drunks jump Cameron again. He defends his wife and himself, running two of the drunk rednecks off. But the third falls, bumps his head, and dies.

At Poe’s trial, the Alabama state judge pronounces that since Poe is a trained Army Ranger and his hands are deadly weapons, he is egregiously guilty of murder. The judge sentences him and sends him away for years. Poe winds up in a federal prison in California…

This is Act I of Con Air, and it’s here that the premise of the movie goes completely off the rails.

For one thing, if you’re a decorated Army Ranger war hero coming home to Alabama, for God’s sake, and you and your beautiful blonde, pregnant wife are assaulted in a parking lot by a group of drunk rednecks who outnumber you three-to-one, and you kill one of them in the process, you’re not going to be arrested for murder.

No, they’re going to put up a statue of you in the town square, give you another medal, and make you the local legend. Hell, they’ll be naming their kids after you.

Second, and this one is a relatively minor plot hole in an otherwise bullet-riddled plot, a state judge in Alabama cannot sentence you to a Federal prison in California. It just doesn’t work that way.

And guess what? Doesn’t matter. I still love the movie and have watched it so many times I can speak the lines back to the screen.

So you see, a solid, airtight plot isn’t necessary for a story to work. The only thing you have to do is write it so well that your reader or audience doesn’t notice until after the movie’s over or they’ve read the last page. By then, it’s too late.

Still, I’m glad I got that whole “how many years does it take to make Captain?” thing right.